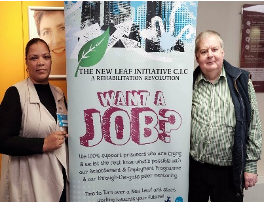

Marie-Claire O’Brien is the Award-winning Founder and CEO of The New Leaf Initiative C.I.C. who are Prison to Employment specialists and consultation experts based in the West Midlands. Marie-Claire’s personal experience of going to prison over 13 years ago, and the insight this subsequently gave her, led to her setting up a non-profit to support others, away from crime and ultimately, into work.

Much has been written over recent years about the relevance of lived experience in the design and delivery of services. This development has been ground-breaking, opening the doors to policy makers and giving service-users a voice in how to deliver services with more efficacy and by whom, whilst challenging decision-makers and the system by holding them to account. In the field of Criminal Justice, this has never been more important. Stark budget cuts of at least 24% since 2010, and staff reductions of 41% over four years, have made employing younger and inexperienced staff necessary in order to maintain order and regime. This coupled with the National privatisation of various services such as probation, have triggered a National Prison and Probation crisis, witnessing the highest rates of violence, suicide, recalls on license, self-harm and drug-taking ever recorded. This culmination of chaos has meant that statutory services, supporting organisations and the third sector must work smarter rather than harder if they are to tackle the problems so readily reported by mainstream media.

How do we develop community leaders who can influence change?

Despite the positivity surrounding service-user involvement, recent research shines a light on the remaining gaps and long-standing issues with utilising service-users in such a way. Tokenism, as well as fear that they may lose their innovative and solution-focussed way of thinking, instead becoming assimilated into the pervasive problem of ‘The System’ they initially sought to challenge and help to develop, remain topical and raises questions.

How, for example, do we ensure that the people with lived experience of services, past and present, remain congruent and innovative, whilst still assisting the development of their personal and professional growth? What happens post-service-user involvement? How do we develop community leaders who can influence change? What is it that drives such a person to re-enter the world of Criminal Justice when they are finally freed, and how and why do they remain steadfast in the courage of their convictions; determined to support a criminal justice system that, sometimes, seem to remain reticent about true redemption and rehabilitation?

The utilisation of lived experience within the world of Criminal Justice is currently centred around four core themes; Service-user involvement, Peer Mentoring, Employment and Ex-Prisoner Entrepreneurship.

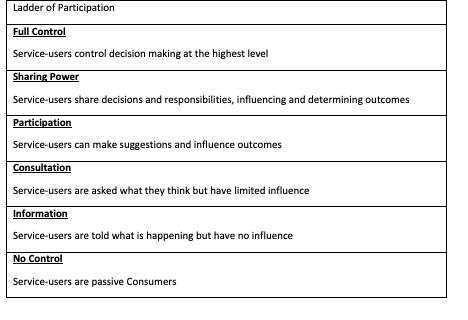

Service-user involvement in relation to people with convictions is identified by Revolving Doors Agency as emulating a ladder of participation:

Motivation and hope are believed to be critical in the early stages of Desistance, and factors which support such changes include someone believing in the individual, distance from the label of offender, and an internal narrative which identifies a more constructive, less stigmatised role.

Despite the lack of robust empirical data on peer mentoring’s efficacy in reducing re-offending, the utilisation of the lived experiences of former prisoners and people with convictions by National organisations such as St Giles Trust and the Princes Trust shows an appetite for such individuals and their engagement skills.

St Giles state that clients who participate in their mentoring programmes show recidivism rates of 40% less than the National average. In a Princes Trust report, 65% of young people interviewed said they would like mentors to help them reduce reoffending, and of those, 71% said they would prefer someone with previous convictions whom they could relate to.

Despite this knowledge, there is still scepticism from some prison and probation staff, and organisations utilising volunteers in custody. In Clinks Report, Valuing Volunteers in Prison, 15% of those interviewed felt that having a criminal record was likely to affect the chance of successfully integrating into the prison to provide support, and in the service-user focus groups conducted for the report, some ex-service-users reported positive responses from staff, whilst others indicated negative reactions.

Baljeet Sandhu is a leading expert on the topic of lived experience and the need to equitably value service users who engage in trying to shape and change the systems that have either helped, or often, hindered them. She categorised three different levels of lived experience utilisation;

- Lived experience, being direct, first-hand experience, either past or present of a social issue and/or injustice

- Lived expertise, defined as knowledge, insights, understanding and wisdom gathered through lived experience.

- Lived experience leaders, change-makers and innovators who activate their lived expertise to inform, shape and lead their social purpose work to directly benefit the community they share those experiences with.

Instead people with lived experience are often viewed as ‘tokenistic informants’ rather than change-makers or leaders of change.

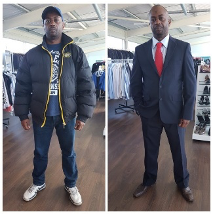

Baljeet's report shines a light on some of the issues around the social sectors inability or unwillingness to value lived experience in equitable and meaningful ways. Instead people with lived experience are often viewed as ‘tokenistic informants’ rather than change-makers or leaders of change. There is a push to volunteer, and this is not to be negated as a worthless pastime – upskilling and confidence building are an essential part in any personal development journey; but developing leaders with lived experience is also essential if socially impactful organisations and institutions are to remain congruent; willing to listen, act upon and employ the troubleshooting insights of those who have been through the system and emerged successfully on the other side. The opportunity to engage in generative activities such as mentoring, volunteering and employment has been shown to reduce the effects of a stigmatised identity, re-establish a sense of worth and a sense of citizenship.

However the road to employment for people with convictions is often not an easy transition. A 2010 survey by Working Links of 300 employers found that only 18% had hired someone with a criminal conviction during the previous three years, and almost three quarters admitted that a conviction disclosure would culminate in rejection of that applicant in favour of a similarly qualified candidate without convictions. An obvious solution to this barrier is the prospect of self-employment and entrepreneurship.

Examples of user-led organisations pepper the world of social entrepreneurship, and leaders with lived expertise have been affecting change world-wide through policy, practise and research for centuries. Security and credibility concerns have dominated this movement within the field of criminal justice, restricting the growth that other sectors, such as mental health, social justice and community development have welcomed. The risk averse culture within Criminal Justice Institutions have meant that instances of visible leaders with lived experience have only just, during the last decade or so, begun to appear, with contractual opportunities rare due to a perceived inability to adhere to statutory requirements around processes, procedures or contractual issues regarding the historic convictions of staff members.

Despite this, there are many successful and credible ex-prisoner led organisations such as Women in Prison founded by Chris Tchaikovsky, User Voice founded and led by Mark Johnson, Intuitive Thinking Skills founded by Zack Haider and Peter Bentley, Prosper4 by Michael Corrigan, Email-a-Prisoner by Derek Jones, the Convict Criminology UK movement led by Rod Earle and Andreas Aresti and colleagues, and a plethora of other long-standing and emerging organisations, including my own, The New Leaf Initiative C.I.C. and many others in the West Midlands.

Tokenism is a widely reported issue with service-user involvement from both participants and facilitators, who can see it as a box-ticking exercise to keep funders at bay, used as evidence that communities are involved in decision-making processes when this is not the case. In a study that I conducted with 45 lived experience leaders, this was vocalised.

James: “I’ve looked at organisations when they are bidding for business, they do it in such a cliched way to keep the commissioner happy – it’s not meaningful, and also when it is consultation it’s often service-user consultation, they forget that your perspective when you’re ‘in’ is different to when you’re ‘out’, so they’re consulting with people who are in the system but how often do they talk to someone who has been out for 10-15 years and ask the question”

This issue of valuable reflection is very current. The lack of hierarchical views of people who have exited the system and have been successful in their attempts to rehabilitate and create solutions for those still trapped based on their own experiences of what doesn’t work, is integral to creating a knowledge-base that decision-makers, such as the West Midlands OPCC can, and I’m pleased to say do, tap into. The social and cultural resources and competence these leaders have, their ability to spot the gaps in service provision based on what they, and their own service-users have experienced, is invaluable. Our unique ability to engage the groups that mainstream providers say are ‘hardest-to-reach’ but who are in fact, crying out to be heard, makes them essential during times of austerity when we must work smarter rather than harder.

Many of us are involved in delivering service-user involvement projects; utilising us can mitigate service user feelings of tokenism, assuming of course that recommendations are actioned, participants are equitably valued, and that any end results are suitably communicated. By not meaningfully and equitably involving experts by experience at the highest levels, we risk failing to understand and grasp the issues at stake for the communities we purport to serve.

Despite the positives of lived experience and the different ways we can engage and invoke change, there also comes with it a necessary burden of responsibility.

For example, my own experiences, particularly as a female ex-prisoner, does not give me the right to speak for everybody’s experiences of prison. This responsibility not to generalise based on our experiences is something that Leaders with Lived experience must balance throughout our careers as change-makers, and especially when feeding into policy.

Instead, utilising critical reflection about our own practise, and the way we convey our views and opinions to decision makers, as well as the issues we seek to challenge and change, is essential. This is the reason consultation with other service users is so important and integral to the creation of an authentic platform, forged from our own experiences, and then going on to share that platform with the communities we serve. It is essential to obtain a rounded view and collective response from our communities, to use our unrivalled engagement skills to listen to the voices of the unheard, before translating what we hear in order to speak truth to power. Without this critical reflection and consultation, the worry is that ego will takeover and the greater good will not prevail.

Nelson Mandela once said “For to be free is not to merely cast off ones chains, but to live in a way that respects and enhances the freedom of others”. That is our duty as leaders with lived experience.

That is our calling.

The New Leaf Initiative are currently preparing to deliver the countries first ever independently evaluated Prison Visitors Council, based on a consultation with 248 visitors, and a Departure lounge at HMP Birmingham, as well as a Co-op which will give employee-ownership to people with convictions. They have supported almost 600 people with convictions via a peer mentoring peer mentoring model since 2014, with 78% entering further education and training, and 40% finding work.