In 2019, I completed an MSc in Public Management, Local Policy and Leadership at the University of Birmingham - part time.

My dissertation explored the role of a Police and Crime Commissioner (PCC) and PCC governance on drug policy, utilising the West Midlands as a case study. This was a real privilege for me, working in this area in my career and being incredibly passionate about developing a harm reduction approach* to drugs.

This blog post gives a very brief summary of the work and its findings.

Police and Crime Commissioners (PCCs) were introduced in 2012, (2011 Police Reform and Social Responsibility Act), representing one of the most radical changes to governance structures in England and Wales followed by the introduction of metro mayors in 2017.

PCCs are directly elected by the public and their statutory functions require them to (1) hold their own police force to account on behalf of the public, (2) set the policing priorities for the area through a police and crime plan and (3) appointing a Chief Constable.

The introduction replaced the previous Police Authority committee style structure, which was criticised for its lack of visibility and accountability to the public and communities they were designed to serve. The emergence of PCCs was therefore a result of the failings of the previous governance mechanism and a political shift of focus from national to local governance (Loveday, 2013; Raine and Keasey, 2012).

The research aimed to establish and assess the impact of PCC governance on drug policy, utilising the West Midlands police force area as a case study. Drugs policy, and specifically a harm reduction approach*, is just one area of policing and priority that was used to explore the statutory role of PCC and more broadly, how the role can be interpreted or used wider than its statutory framework.

In August 2019 the latest drug related death figures were announced by the ONS. They are now the highest on record, with 4359 deaths in England and Wales in 2018 (ONS, 2019). In the West Midlands, there is a death every 3 days (West Midlands PCC 2017a). Over 50% of serious and acquisitive crime is to fund an addiction and the cost to society is over £1.4 billion (West Midlands PCC 2017a). This topic often divides opinion and can be politicised. However, these debates rarely prevent the considerable damage caused by drugs to often very vulnerable people and wider society. The official national response is focused on enforcement of the law; criminalising individuals for drug possession.

Through interviewing a number of key actors within the drug policy arena and as leaders in policing both within forces and PCC offices, the research focused on testing how the PCC can enable a change in policy. This was combined with desk-based document study into the drugs policy approach in the West Midlands through a series of publicly available documents. Four key themes were explored; the statutory role of the PCC, the individual PCC, Governance and public opinion and approach.

Some of the results identified that the PCC role and this new form of civic leadership benefitted from convening power, the ability of a PCC to draw key partners from across the public sector, lived experience, and third sector together. This is an informal mechanism of governance strengthened by public mandate. PCCs have the ability to prioritise, through setting their strategic priorities in a police and crime plan. For example, in the West Midlands, the approach to drug policy has been narrowed to focus on the high harm drugs of heroin and crack cocaine thus ensuring ‘deliverability’, therefore limited resources tackling a narrower scope to achieve a greater impact. The statutory role of a PCC allows work at pace and decisions to be made quickly allowing PCCs to trial and pilot new approaches and innovations.

Of course, there are limitations. PCCs vary across the country and often do not speak with one voice, particularly on drug policy, despite the structures in place for an Association of PCCs. There are also huge advantages of a good working relationship between Chief Constable and PCC, demonstrated through the joint approach in the West Midlands.

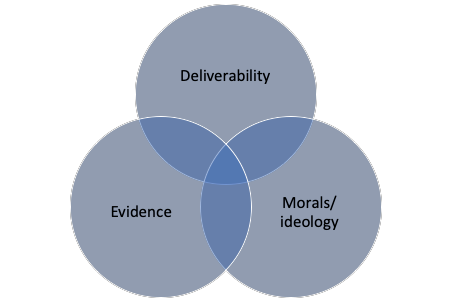

Based on the research, it can be concluded that three key drivers are optimum for delivery of a PCC-led harm reduction approach. PCC governance, utilising the levers at their disposal such as the statutory functions and informal governance mechanism such as convening power are able to provide strategic, political coverage to deliver at pace.

PCCs are unique in the landscape of UK governance and whilst weakness in mechanism for reigning in their power could be viewed as worrying, in the drug policy space this has allowed the development of a new approach in the West Midlands, which is evidence-based and has the ability to save lives, save cost and reduce crime. Leadership and political bravery were a key theme throughout the research, with views from interviewees that this was lacking at a national level to enable a change in government policy.

The potential of PCCs is arguably still being explored, but their ability to test new approaches and work effectively with partners will be essential in other areas of policy such as the response to serious violence and the potential for an increasing role across the criminal justice system.

PCCs have a number of levers at their disposal, utilising informal and formal governance mechanism with an ability to make a real change at a local level, driving forward evidence-based policy. PCCs can be drug policy actors, enabling a harm reduction approach and delivering at pace.

*There are numerous definitions of ‘harm reduction’ in the literature. Here. the researcher utilises Newcombe’s definition:

“Harm reduction — also called damage limitation, risk reduction, and harm minimization — is a social policy which prioritizes the aim of decreasing the negative effects of drug use. Harm reduction is becoming the major alternative drug policy to abstentionism, which prioritizes the aim of decreasing the prevalence or incidence of drug use. Harm reduction has its main roots in the scientific public health model, with deeper roots in humanitarianism and libertarianism. It therefore contrasts with abstentionism, which is rooted more in the punitive law enforcement model, and in medical and religious paternalism”. (Newcombe 1992, 1)

The harm-reduction approach emerged in the 1980s, one of the key drivers was due to the risk of HIV infection. To clarify; A harm reduction approach to drug policy does not mean decriminalisation or legalisation.

For more information and to access the publicly available documents from the West Midlands PCC, please visit:

https://www.westmidlands-pcc.gov.uk/projects/drugs-2/

Megan Jones

Tweets at @MegJ4289.

Sources

Loveday, B. (2013) ‘Police and Crime Commissioners: The Changing Landscape of Police Governance in England and Wales: Their Potential Impact on Local Accountability, Police Service Delivery and Community Safety’ International Journal of Police Science & Management. 15 (1): 22-29. Available from: doi: 10.1350%2Fijps.2013.15.1.298

Raine, J. and Keasey, P. (2012), ‘From Police authorities to police and crime commissioners: might policing become more publicly accountable?’, International Journal of Emergency Services, 1(2), 122-34. Available from: doi: org/10.1108/20470891211275911